Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Mechanical 101: A Complete Beginner’s Guide to How Things Move (2025)

If you’ve ever looked at a bike, a robot arm, or even a door hinge and thought, “I kind of get it… but not really,” this guide is for you.

Mechanical 101 is about understanding how physical things move, carry loads, and not fall apart—using simple ideas, clear visuals in your head, and practical examples instead of pages of equations.

Table of Contents

- 1. What Mechanical Engineering Actually Is

- 2. Forces & Motion (Without the Scary Math)

- 3. Simple Machines: The Building Blocks

- 4. Torque: Twisting Force

- 5. Gears, Speed & Mechanical Advantage

- 6. Bearings & Friction

- 7. Fasteners: Bolts, Nuts, Screws & Threads

- 8. Materials: Steel, Aluminum, Plastics & More

- 9. Loads, Stress & “Why Things Break”

- 10. Joints, Linkages & Motion Conversion

- 11. 3D Printing & Prototyping for Mechanicals

- 12. Mechanical Safety 101

- 13. Beginner Mechanical Projects (Great First Builds)

- 14. Mechanical 101 Learning Roadmap

- Final Thoughts

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

1. What Mechanical Engineering Actually Is

Mechanical engineering is the study of:

- Forces – pushes and pulls

- Motion – how things move and rotate

- Energy – how power is stored, transferred, and used

- Materials – what things are made of and why

- Mechanisms – how parts connect to do useful work

Anything that moves or carries a load has mechanical design behind it:

- Bikes, cars, drones

- 3D printers, CNC machines, robots

- Doors, latches, tools, hinges

- Engines, pumps, fans

If electronics are the “nerves and brain,” mechanics are the bones and muscles.

2. Forces & Motion (Without the Scary Math)

You already understand mechanical basics from everyday life—you just may not have the words yet.

2.1 Force

A force is a push or a pull.

Examples:

- Pushing a door open

- Gravity pulling a book down

- A motor pulling a belt

We usually care about:

- How big the force is

- Where it’s applied

- Direction of the force

2.2 Newton’s “Common Sense” Laws

In beginner language:

- Things like to keep doing what they’re already doing.

- If it’s still, it wants to stay still.

- If it’s moving, it wants to keep moving straight.

- Acceleration happens when a force doesn’t balance out.

- Push harder → it speeds up more.

- More mass → harder to accelerate.

- For every push, there’s a push back.

- When you stand on the floor, you push down and the floor pushes up.

You don’t need equations yet—just understand:

If things move, some force made them move.

If things don’t move, forces are balanced.

3. Simple Machines: The Building Blocks

Long before robots, humans used simple machines to make work easier. They’re still everywhere in modern designs.

3.1 Levers

Seesaws, crowbars, pliers, and wrenches are all levers.

A lever lets you trade distance for force:

- Push a long handle a big distance → move the heavy end a small distance with big force.

3.2 Inclined Plane

A ramp.

Instead of lifting something straight up, you slide it up over a longer distance with less force.

3.3 Pulleys

Use ropes and wheels to lift loads more easily or change direction of force.

3.4 Wheel & Axle

Wheels on cars, gears, doorknobs—turning a wheel makes it easier to rotate an axle with more force.

3.5 Screws

A screw is basically an inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder. It turns rotational motion into linear motion with big force (clamps, jacks, bolts).

Once you see these patterns, you start spotting simple machines everywhere.

4. Torque: Twisting Force

Torque is the mechanical idea behind wrenches, bike pedals, and door handles.

Torque = Force × Distance from the pivot

You feel this when:

- It’s easier to loosen a bolt with a longer wrench.

- A door is easier to open when you push far from the hinge.

Key intuition:

- More force or longer handle → more torque.

- Short handle → you need more force.

When designing mechanisms, you’re always thinking:

“Do I have enough torque to turn this?”

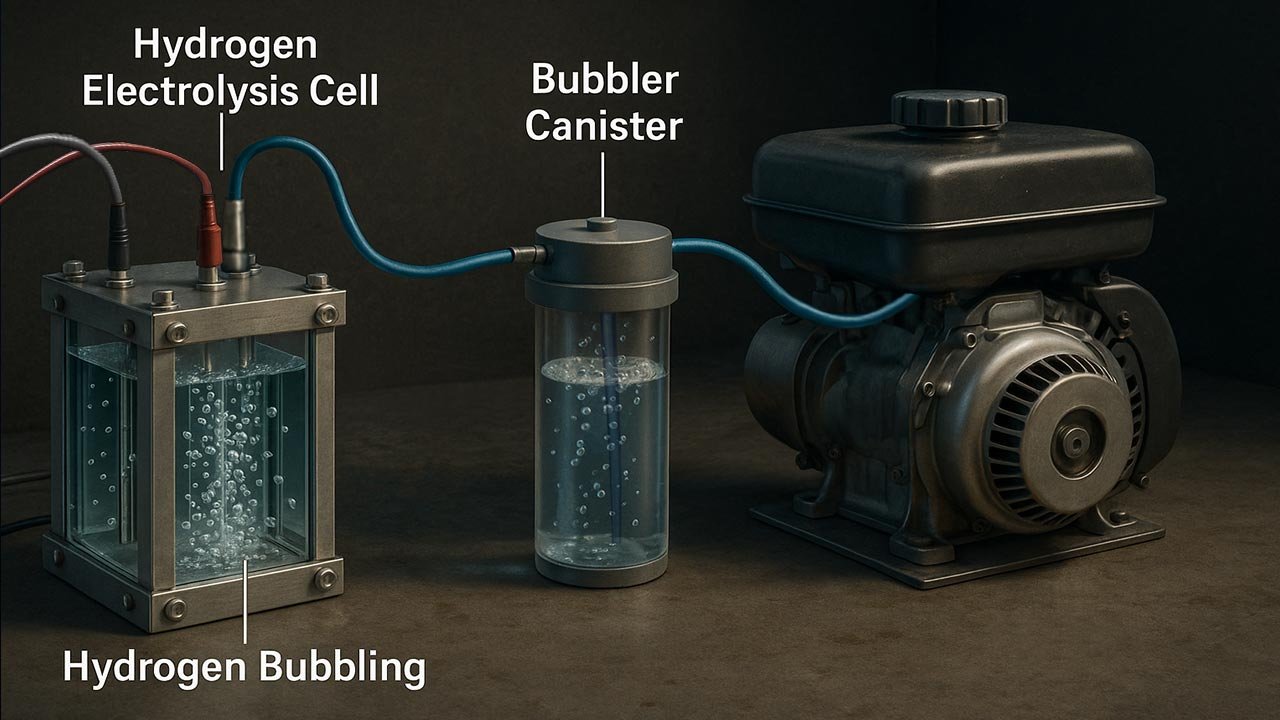

5. Gears, Speed & Mechanical Advantage

Gears are toothed wheels that mesh together to:

- Change speed

- Change torque

- Change direction of rotation

5.1 Gear Ratio (Intuitive Version)

If a small gear drives a large gear:

- Large gear turns slower

- But with more torque

If a large gear drives a small gear:

- Small gear turns faster

- With less torque

So:

- Use bigger driven gears when you need more force (e.g., robots climbing, winches).

- Use smaller driven gears when you need more speed (e.g., fans, some tools).

6. Bearings & Friction

If things move, friction fights them.

Friction can be:

- Your friend (car tires gripping the road)

- Your enemy (things overheating, wasting energy)

6.1 Bearings

Bearings reduce friction between moving parts.

Common types:

- Ball bearings – balls roll between inner and outer rings

- Sleeve / bushing – shaft slides in a low-friction material

- Roller bearings – small cylinders for higher loads

As a rule of thumb:

- Use ball bearings for rotating shafts in robots, wheels, motors.

- Use bushings where speeds are low and loads are moderate.

7. Fasteners: Bolts, Nuts, Screws & Threads

Things rarely stay together without fasteners.

7.1 Screws vs Bolts

- Screw – usually goes into a threaded hole (or forms its own thread in plastic/wood).

- Bolt – usually goes through parts and is secured with a nut.

7.2 Why Threads Matter

Threads convert twisting torque into clamping force.

Key beginner tips:

- Don’t over-tighten → you can strip threads, especially in plastic.

- Use washers to spread load on softer materials.

- For vibration-heavy projects, use locknuts or thread-locking fluid.

8. Materials: Steel, Aluminum, Plastics & More

You don’t need full material science, just basic instincts:

8.1 Steel

- Strong, stiff, heavy

- Great for structural parts, shafts, tools

- Rusts if uncoated

8.2 Aluminum

- Lightweight, fairly strong

- Good for frames, brackets, robot arms

- Easy to machine

- Not as stiff as steel, may bend more

8.3 Plastics (e.g., PLA, ABS, PETG, Nylon)

- Great for 3D-printed and low-load parts

- Lightweight, easy to shape

- Not as strong or stiff as metals

- Some handle heat and impact better than others

Rule of thumb:

- Metals for critical, high-load, or safety parts.

- Plastics for enclosures, light brackets, or prototypes.

9. Loads, Stress & “Why Things Break”

Beginner mindset:

Parts fail when stress (force spread over area) gets too high or repeats too many times.

9.1 Types of Loads

- Tension – pulling apart

- Compression – squeezing

- Shear – sliding layers past each other

- Bending – combination of tension & compression

- Torsion – twisting (shafts, axles)

You don’t need formulas yet—just ask:

- Where is this part being pushed or pulled?

- Where is it most likely to bend or crack?

- Can I make it thicker, add a brace, or change material?

9.2 Safety Factor (Beginner Version)

Because real life is messy, we design for more than the expected load.

If your part must handle 50 kg, you might design for 100 kg to be safe.

This is the safety factor concept.

10. Joints, Linkages & Motion Conversion

Many mechanisms are just clever ways of linking parts.

10.1 Common Joints

- Pin/hinge joint – rotates about one axis (door hinge, robot arm elbow)

- Slider joint – moves in a straight line (drawer slide)

- Fixed joint – no motion (welds, glued, tightly bolted)

10.2 Linkages

Linkages convert one type of motion into another.

Examples:

- Crank–slider – converts rotation to linear motion (engine piston, some pumps)

- Four-bar linkage – can produce near-straight motion or complex paths

- Cam & follower – converts rotation to a custom motion pattern

Once you start seeing linkages, you’ll notice them in tools, printers, folding mechanisms, etc.

11. 3D Printing & Prototyping for Mechanicals

Modern mechanical beginners have a secret weapon: 3D printing.

Why It’s Amazing

- Quickly test shapes and mechanisms

- Cheap to iterate – print, test, tweak, reprint

- Combine with off-the-shelf hardware (bearings, bolts, motors)

Beginner tips:

- Design with thickness in mind (don’t make thin walls for high-load parts).

- Consider layer directions – parts are weaker between layers.

- Use test prints for critical fits (bearings, shafts, screw holes).

12. Mechanical Safety 101

Mechanical things can hurt you if you’re careless. Basic rules:

- Keep fingers, hair, and clothing away from moving parts.

- Always power down before adjusting mechanisms.

- Use eye protection when cutting, drilling, or grinding.

- Don’t overload tools or parts “just to see what happens.”

- Treat springs, press-fit parts, and high-tension assemblies with respect—they can snap or release energy suddenly.

Good habits early prevent bad days later.

13. Beginner Mechanical Projects (Great First Builds)

These project ideas teach real fundamentals without needing a full workshop:

- Lever-powered grabber tool

- Learn levers, linkages, grip force.

- Rubber-band powered car

- Learn wheels, axles, friction, energy storage.

- Simple gear train with 3D-printed gears

- Learn gear ratios, torque vs speed.

- Adjustable phone stand with hinges

- Learn pivots, friction joints, fasteners.

- Crank and slider desk toy

- Learn motion conversion, linkages.

- Small 3D-printed robot chassis

- Learn structural design, mounting holes, center of gravity.

Each project can start simple and become more “engineer-y” as you refine and iterate.

14. Mechanical 101 Learning Roadmap

Here’s a practical path from “total beginner” to “I can design simple mechanisms.”

- Learn the language

- Forces, torque, simple machines, materials, basic joints.

- Take things apart

- Old printers, toys, tools—study how they move and are assembled.

- Build small prototypes

- Cardboard, 3D prints, wood, simple hardware.

- Experiment with gears, levers, and linkages

- Try changing lengths, positions, and see how it affects motion.

- Study real designs

- Bikes, hinges, scissor lifts, folding mechanisms; sketch them.

- Learn basic CAD

- Tools like Fusion 360, Onshape, or FreeCAD to model parts.

- Combine with electronics

- Add motors, servos, and sensors to your mechanical creations.

- Design for reliability

- Think about loads, wear points, and safety factors.

Over time, your instincts sharpen: you start feeling when a part is too thin, a lever too short, or a joint likely to bind.

Final Thoughts

Mechanical engineering isn’t just about formulas and complex simulations. At its heart, it’s about understanding how the physical world moves, then shaping it to do useful, clever, or just plain fun things.

You don’t need a degree to start thinking like a mechanical engineer. You need:

- Curiosity about how things work

- Willingness to build and break prototypes

- A habit of noticing forces, motion, and materials around you

Welcome to Mechanical 101.

Now go build something that moves.

Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related Mechanical Learning…

How to Get Started Learning Mechanical Skills

How to Get Started Learning Mechanical Skills Learning mechanical skills is one of the [...]

Hydrogen From Water to Horsepower

Hydrogen From Water to Horsepower: The Real Story Behind HHO and 4-Stroke Engines Todays [...]

How Mechanical Systems Work

DIY Hobby Maker’s Guide: How Mechanical Systems Work How mechanical systems work, forces, motion, [...]

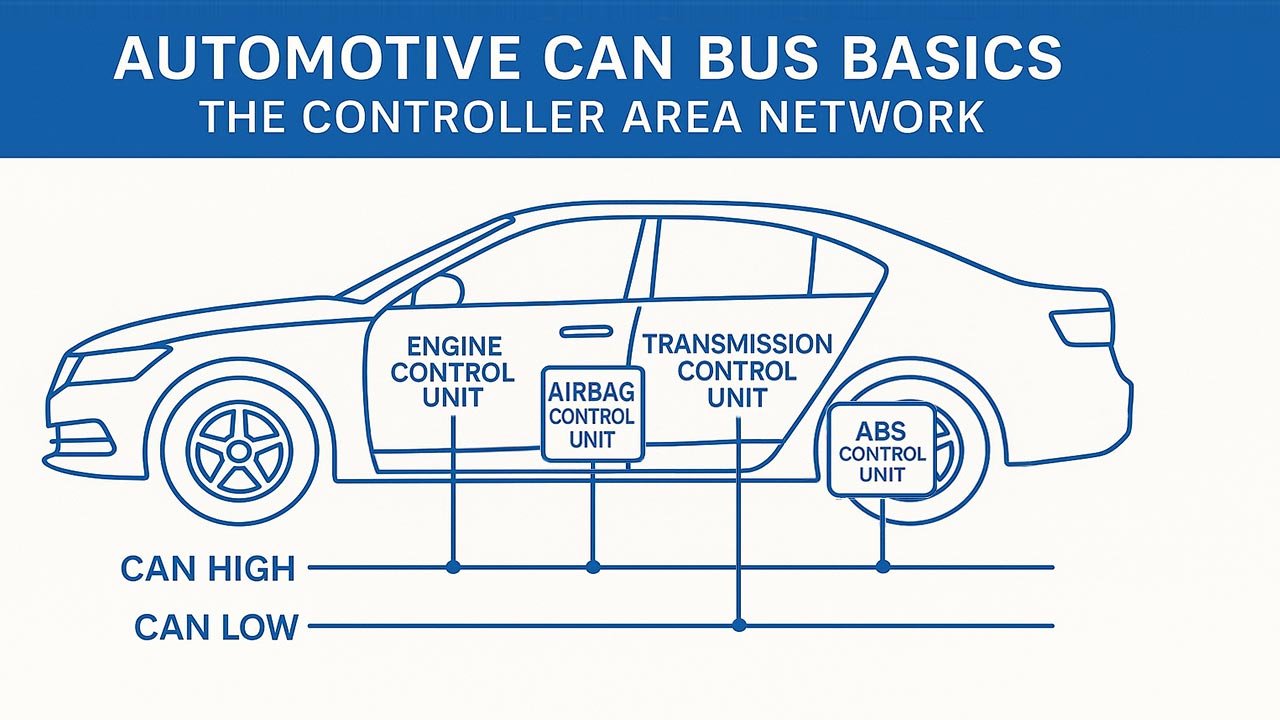

Automotive CAN Bus Basics

Automotive CAN Bus Basics: The Controller Area Network The Controller Area Network (CAN [...]

Related 101 Topics…

Continue Learning other DIY topics…

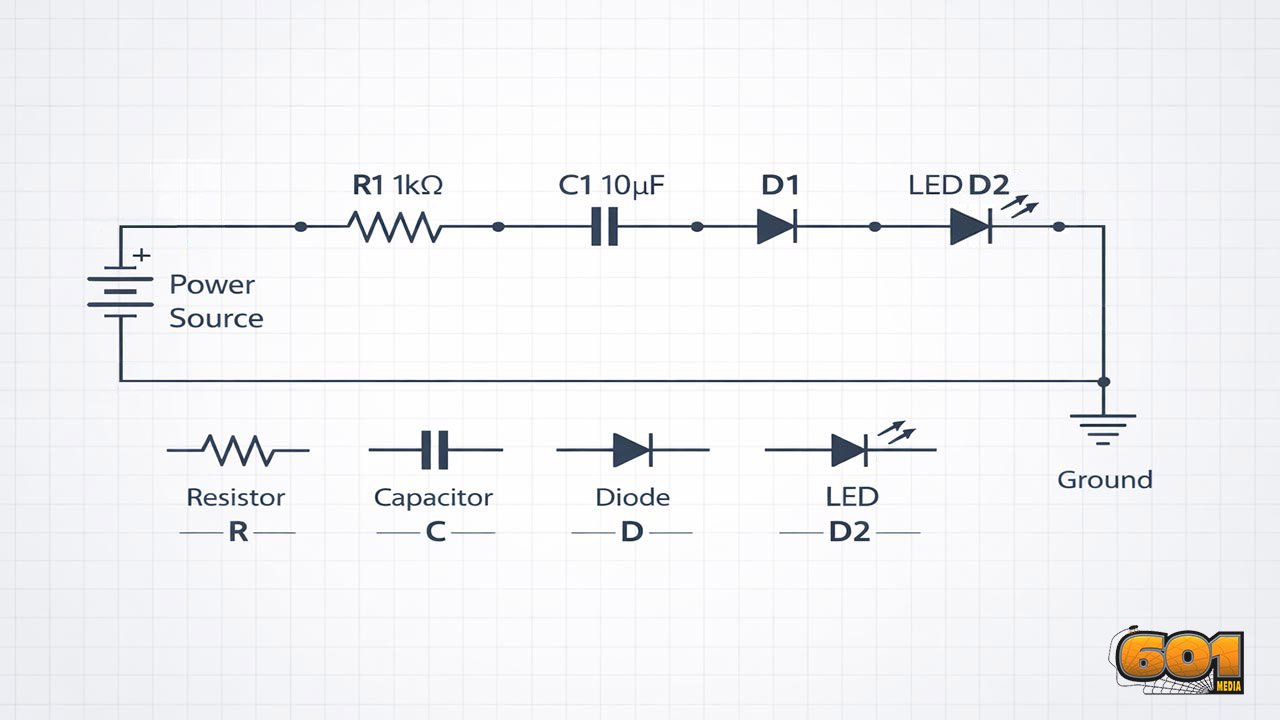

Circuit Diagrams for Beginners

Circuit Diagrams for Beginners: How to Read and Draw Schematics Understanding circuit diagrams is [...]

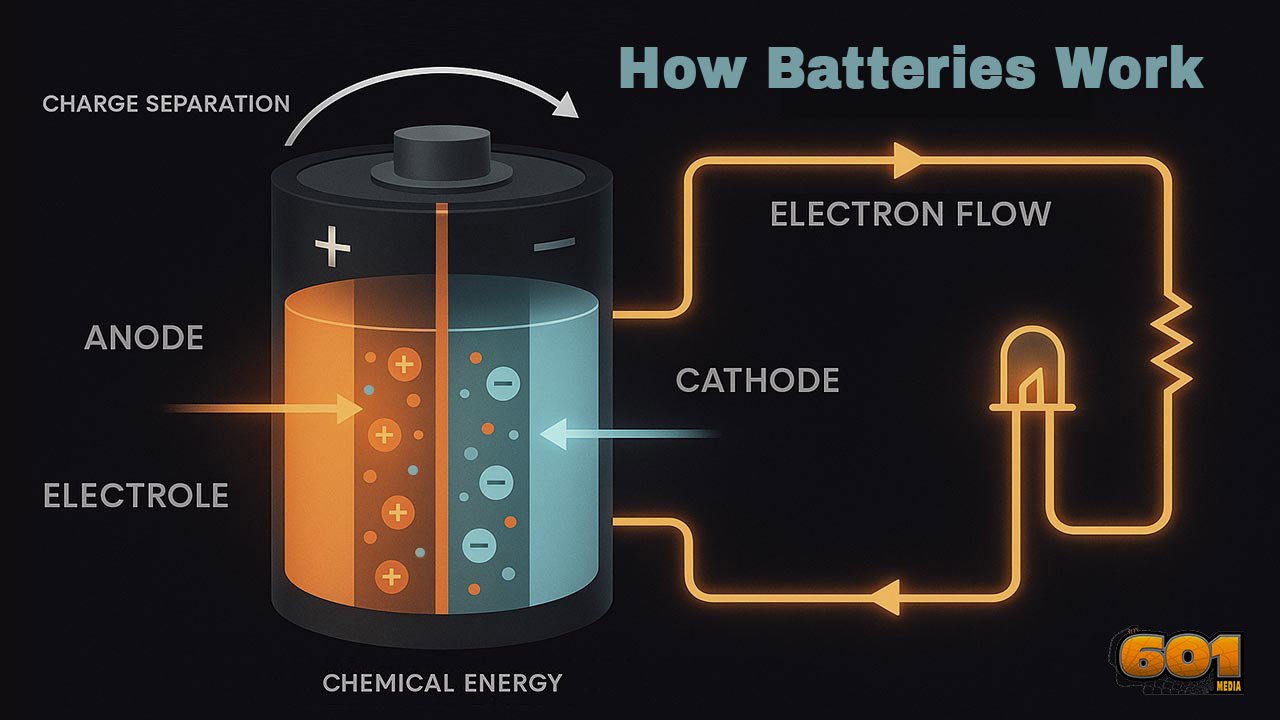

How Batteries Work

How Batteries Work: Charge Separation, Electron Flow, and Chemical Energy A practical deep-dive into [...]

Power Electronics: How It Works, Why It Matters, and Where It’s Headed Next

What Is Power Electronics? Power Electronics: A concise exploration of the field that controls, [...]

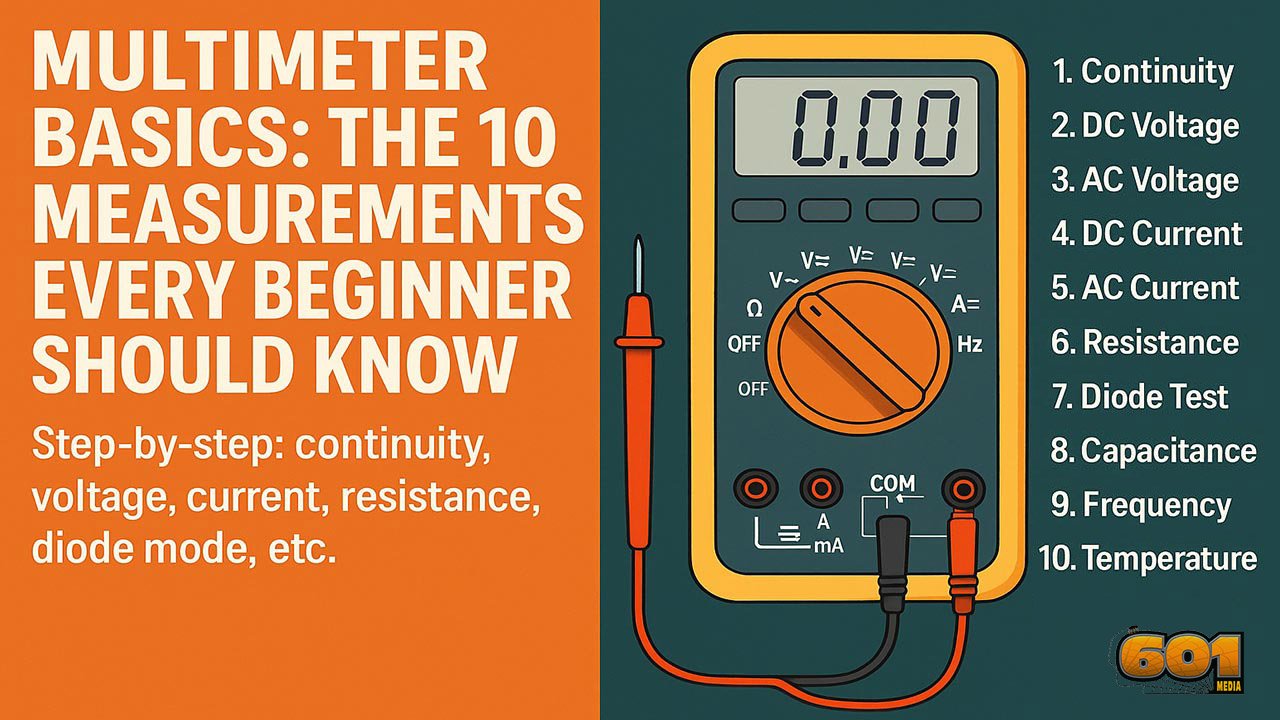

Multimeter Basics

Multimeter Basics: The 10 Measurements Every Beginner Should Know Learn the ten multimeter functions [...]

Godot Game Engine vs. Unity

Godot Game Engine vs. Unity: A Comparison for Modern Game Development Godot and Unity [...]

How to Get Started Learning IoT Automation

How to Get Started Learning IoT Automation IoT automation is transforming how industries operate, [...]

Headquarters:

601MEDIA LLC United States