Hydrogen From Water to Horsepower: The Real Story Behind HHO and 4-Stroke Engines

Todays article unpacks the real engineering behind HHO (oxyhydrogen) systems, how they interact with 4-stroke internal combustion engines, what peer-reviewed research actually shows about fuel savings and emissions, and why—despite decades of hype—HHO has not become a mainstream automotive technology.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why HHO Won’t Go Away

- What Exactly Is HHO?

- How a 4-Stroke Engine Really Uses Fuel

- The Energy Balance Problem: Does HHO Increase MPG?

- Where HHO Can Actually Help

- Witness the Video Proof

- What the Research Really Says

- Innovation and Technology Management View

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts

- Resources

Introduction: Why HHO Won’t Go Away

HHO, often called “Brown’s gas” or oxyhydrogen, has been promoted for years as a way to turn plain water into extra horsepower and better mileage. The story usually goes like this: install a low-cost electrolysis unit under the hood, split water into hydrogen and oxygen using your car’s alternator, pipe that gas into the intake, and enjoy dramatic fuel savings.

From an innovation and technology management perspective, this idea is irresistible: cheap retrofit, no infrastructure change, and a green halo. If it worked as advertised, automakers, fleets, and regulators would be all over it. Yet, despite decades of claims, there is no mass-market, OEM-backed HHO solution for 4-stroke road engines. That gap between promise and adoption is the core of the “real story.”

To understand why, we need to look at three things together: how HHO is produced, how a 4-stroke engine actually uses energy, and what rigorous research shows about the trade-offs between additional electrical load, hydrogen production, and combustion effects.

What Exactly Is HHO?

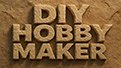

Electrolysis Explained Simply

HHO systems use electrolysis of water. When you pass an electric current through water containing an electrolyte, water molecules split into hydrogen (H₂) and oxygen (O₂). This is a well-understood industrial process. Modern electrolyzers, depending on technology, typically operate with efficiencies in the range of roughly 60–80% when converting electrical energy into chemical energy in hydrogen.

In a vehicle retrofit, that electrical power is drawn from the alternator. The alternator is powered mechanically by the engine crankshaft. That means every amp you use to generate HHO ultimately costs you fuel at the crankshaft.

HHO vs. Pure Hydrogen

It is important to distinguish HHO from pure hydrogen:

- HHO (oxyhydrogen): Mixed gas containing hydrogen, oxygen, and water vapor, produced and used immediately, usually at low pressure.

- Pure hydrogen: Typically compressed or liquefied, stored separately from oxygen, and used either in fuel cells or in carefully designed hydrogen-ICE engines.

Fuel-cell vehicles and industrial hydrogen applications almost always use pure hydrogen, not HHO. They are optimized around high-efficiency electrolysis or reforming and high-efficiency conversion in fuel cells, not a small on-board cell feeding a conventional gasoline engine.

How a 4-Stroke Engine Really Uses Fuel

The Four Strokes in Plain Language

A 4-stroke spark-ignition (SI) engine works in a loop of four piston movements:

- Intake: The intake valve opens, and the piston moves down, drawing in air and fuel (plus any HHO if installed).

- Compression: The valves close, and the piston moves up, compressing the mixture.

- Power: The spark plug ignites the mixture. The rapid expansion of hot gases drives the piston down and produces useful work.

- Exhaust: The exhaust valve opens, and the piston moves up again, pushing burnt gases out.

HHO is typically introduced into the intake air stream, so it becomes part of the combustible mixture that is compressed and ignited during the power stroke.

Engine Efficiency and Where Energy Goes

Internal combustion engines are heat engines. Only a fraction of the chemical energy in fuel turns into wheel torque; the rest is lost as heat, friction, and pumping work. Modern production spark-ignition engines typically reach a brake thermal efficiency (BTE) of about 30–36%, with advanced designs and operating points occasionally exceeding 40%.

This means that if you put 100 units of energy into the engine as fuel, perhaps 30–40 units become mechanical work at the crankshaft, and the rest is lost. Any additional electrical load (like an HHO cell) must be supplied from that same mechanical output.

So, when evaluating HHO, we have to look at the entire energy chain from gasoline to crankshaft to alternator to electrolysis cell and back into combustion. Each step has its own efficiency losses.

The Energy Balance Problem: Does HHO Increase MPG?

The central technical question is not “can hydrogen burn?”—it obviously can—but rather “does on-board HHO generation create a net fuel-economy gain once all losses are included?”

Alternator Load: The Hidden Horsepower Tax

Vehicle alternators are not lossless machines. Modern automotive alternators typically achieve around 70–80% efficiency at moderate speeds, though real-world values and older designs can be lower.

That means supplying 300 W of electrical power to an HHO cell might require something like 375–430 W of mechanical power at the crankshaft. To provide that mechanical power, the engine must burn more fuel.

From a management lens, that extra load is a hidden horsepower tax. Even if HHO combustion slightly improves how completely the gasoline burns, it must first pay back the fuel used to turn the alternator harder.

Electrolysis Efficiency and Compounded Losses

Electrolysis itself is also not perfectly efficient. Contemporary electrolysis technologies for hydrogen production often operate at roughly 60–80% efficiency under optimized conditions.

Now combine the two chains:

- Engine converts fuel to mechanical power (say 30–36% efficient).

- Alternator converts mechanical power to electrical power (~70–80% efficient).

- Electrolyzer converts electrical power to chemical energy in hydrogen (~60–80% efficient).

Multiplying these stages together gives a very low overall pathway efficiency from gasoline energy to HHO energy. That is before we even consider how effectively that small amount of HHO actually improves combustion.

This cumulative loss is why rigorous theoretical analyses of on-board HHO production generally conclude that there is no credible pathway to significant net fuel-economy gains in conventional 4-stroke engines when the system is powered by the same engine it is supposed to improve.

Combustion Dynamics With HHO Injection

Hydrogen has a very wide flammability range and high flame speed. Adding small amounts of HHO to a gasoline–air mixture can:

- Promote faster flame propagation.

- Enable more complete combustion of hydrocarbons in some conditions.

- Influence ignition timing and knock behavior.

Several studies show that hydrogen or HHO enrichment can reduce carbon monoxide (CO), unburned hydrocarbons (HC), and particulate emissions by improving burn quality.

However, the amount of HHO typical retrofit systems can generate—while constrained by alternator capacity and driver comfort—is usually very small relative to the mass of air ingested by a 4-stroke engine at real-world loads. That limits how much combustion can realistically be changed.

In other words, the chemistry is not the issue. The bottleneck is energy and mass flow: you cannot inject enough HHO, generated from the same fuel source, to overcome the upstream losses without violating basic thermodynamics.

Where HHO Can Actually Help

Emissions and Burn Quality

Several experimental studies, especially in controlled lab setups, have reported:

- Reduced CO and HC emissions.

- Improved combustion stability at certain loads.

- Occasional reductions in specific fuel consumption (SFC) under tuned conditions.

One study on SI engines with HHO supplementation reported meaningful reductions in emissions and improvements in fuel economy when hydrogen was carefully metered and operating conditions were stable. Another review of HHO use in engines found reduced consumption of traditional fuels (20–30% in some test configurations) and lower HC and CO emissions, but under structured test conditions and with external or fixed-load setups that do not perfectly represent passenger vehicles in daily use.

From a technology management perspective, these results are interesting because they suggest HHO can work as a combustion modifier—a way to tune emissions and stability—rather than as a free energy source.

Niche Use Cases and Lab Conditions

HHO tends to look more promising when:

- The engine runs at constant speed and load (for example, generators or test benches).

- Researchers can design around external power supplies for electrolysis, decoupling HHO production from engine fuel use.

- The objective is emissions control rather than dramatic MPG gains.

In those situations, improvements up to several percent in fuel consumption and noticeable emissions reductions have been reported. But that is a very different business case from promising drivers 30–50% better mileage from a simple under-hood retrofit on a daily-driven 4-stroke car.

Witness the Video Proof

Here’s a video of a full build on a small generator showing what’s possible.

Stanley Meyer did it and Arrington Performance has done it too… watch the video below to witness the proof.

What the Research Really Says

Studies That Show Benefits

Recent experimental work on engines enriched with HHO reports:

- Reduced specific fuel consumption in controlled conditions.

- Increased torque and power in some operating ranges.

- Lower CO and HC emissions and sometimes lower soot.

These benefits are often observed in laboratory test rigs where flow rates, ignition timing, mixture preparation, and load are carefully controlled. In many cases, the energy cost of HHO production is not fully integrated into a whole-vehicle fuel economy model, or HHO is powered from the grid rather than from the engine’s own fuel.

Studies That Question On-Board Feasibility

In contrast, theoretical and systems-level analyses that account for the entire energy chain—including alternator and electrolysis losses—tend to be much more skeptical. A detailed energetic study of on-board HHO production and use as a fuel additive concluded that once all losses and practical limits are included, on-board HHO cannot deliver net fuel savings in typical engine configurations.

When you combine that with known engine efficiency limits and alternator behavior, the pattern is consistent: HHO is not a free energy source. At best, it is a tunable combustion aid whose benefits are bounded by the physics of the entire drivetrain.

Innovation and Technology Management View

Why HHO Hasn’t Been Commercialized at Scale

If HHO could reliably deliver 20–50% fuel savings in real-world 4-stroke engines, major OEMs and Tier-1 suppliers would have powerful incentives to adopt it: regulatory compliance, competitive advantage, and clear cost savings for fleet customers.

Yet the market reality is the opposite. Large automakers focus on:

- High-efficiency gasoline and diesel engines with advanced combustion strategies.

- Hybridization and electrification.

- Dedicated hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles and hydrogen ICEs using pure hydrogen, not oxyhydrogen add-ons.

From an adoption standpoint, this suggests that the evidence for large, robust, field-tested HHO gains is insufficient to justify the engineering, warranty, and safety risks that OEMs would need to absorb.

Barriers to Adoption and Regulation

Several practical barriers also slow HHO adoption:

- Safety: HHO is highly combustible. Poorly designed systems can pose flashback and leak risks. Engineering robust, certified systems adds cost and complexity.

- Measurement and validation: Proving real-world fuel savings to regulators and fleet buyers requires standardized test cycles and repeatable results.

- Economic ROI: If the net fuel savings are small, the business case for adding cost, maintenance, and risk is weak.

- Competing technologies: Hybrids, battery EVs, and dedicated hydrogen technologies are backed by substantial policy and infrastructure momentum.

Future Potential of On-Board Hydrogen Systems

Despite these challenges, research into hydrogen-assisted combustion is far from dead. Promising directions include:

- High-efficiency electrolysis: Continued advances in PEM and solid-oxide electrolyzers improve efficiency and may eventually support more compelling on-board use cases, especially when paired with waste-heat recovery or hybrid architectures.

- Dedicated hydrogen-ICE concepts: Engines optimized specifically for hydrogen (not gasoline plus retrofitted HHO) could leverage hydrogen’s properties to reach very high efficiencies and low emissions.

- Integrated hybrid systems: Combining batteries, regenerative braking, and perhaps limited on-board hydrogen generation may create niche architectures where hydrogen plays a role in combustion shaping rather than as a main energy carrier.

From an innovation management standpoint, the likely future of HHO-type concepts is not as miracle retrofit kits for existing cars, but as research stepping stones toward more integrated hydrogen and hybrid powertrains.

Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Final Thoughts

The most important takeaway is this: HHO cannot escape thermodynamics. The idea of unlocking “free energy from water” inside a conventional 4-stroke engine is appealing, but the complete energy chain tells a different story.

When fuel is burned in the engine, only a fraction of its energy becomes mechanical output. Part of that output must drive the alternator, which loses more energy as heat while converting mechanical power to electricity. Electrolysis then incurs additional losses converting electricity into hydrogen and oxygen. By the time a small volume of HHO reaches the combustion chamber, it is carrying only a small slice of the original fuel energy.

Hydrogen’s combustion properties are genuinely useful: it can accelerate flame speed, widen the flammability range, and reduce certain emissions when carefully applied. Research supports these roles, especially in controlled or specialized setups. But in the mainstream automotive world, energy-dense gasoline, hybridization, and dedicated hydrogen technologies offer clearer, scalable pathways to higher efficiency and lower emissions.

From an innovation and technology management angle, HHO today looks less like a suppressed miracle and more like a technology whose niche benefits and hard physical limits have become clearer with rigorous research. The real opportunity is to carry the lessons from HHO—about hydrogen’s effect on combustion and system-level energy accounting—into the design of future integrated hydrogen and hybrid powertrains, rather than expecting a simple under-hood retrofit to rewrite the rules of engine efficiency.

Resources

- Polverino, P. et al. “Study of the energetic needs for the on-board production and use of oxy-hydrogen (HHO) as a fuel additive in internal combustion engines.” Energy, 2019.

- Yue, M. et al. “Hydrogen energy systems: A critical review of technologies, applications, and market outlook.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2021.

- Guerrero-Rodríguez, N. F. et al. “An Overview of the Efficiency and Long-Term Viability of Hydrogen Electrolysis Technologies.” Sustainability, 2024.

- Liu, H. et al. “Investigation on the Potential of High Efficiency for Internal Combustion Engines.” Energies, 2018.

- Kazim, A. H. and others. “Effects of oxyhydrogen gas induction on the performance of a spark-ignition engine.” Various experimental studies, 2020–2024.

- Technical summaries on alternator efficiency and vehicle electrical loads.

Leave A Comment