Understanding Resistors (and Why Every Circuit Uses Them)

Understanding resistors is the fastest way to understand electronics itself. Every electronic system, from a simple LED toy to a cloud data center, relies on resistors to control, protect, and stabilize electrical behavior. This article explains what resistors do, how they work, why they are unavoidable in circuit design, and how engineers choose the right one for the job.

Table of Contents

- What Is a Resistor?

- Why Resistors Are Essential in Every Circuit

- How Resistors Work at the Physical Level

- Types of Resistors and Their Use Cases

- Resistor Values, Tolerances, and Ratings

- Resistors in Real-World Circuit Design

- Common Mistakes When Using Resistors

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts

- Resources

What Is a Resistor?

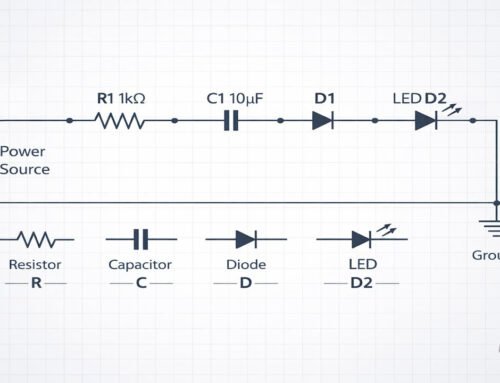

A resistor is a passive electronic component that limits the flow of electric current. Its job is not to create energy or store it, but to control how electricity behaves as it moves through a circuit. By opposing current, resistors make electronic systems predictable, safe, and functional. In technical terms, a resistor converts electrical energy into heat according to a proportional relationship between voltage and current. This relationship is formalized by Ohm’s Law, which states that voltage equals current multiplied by resistance. This simple rule underpins nearly all circuit analysis in electrical engineering. Without resistors, most electronic components would instantly fail. LEDs would burn out, transistors would short themselves, and integrated circuits would experience destructive current spikes.

Why Resistors Are Essential in Every Circuit

Resistors appear in almost every schematic because they solve several fundamental engineering problems at once.

First, they limit current. Semiconductor devices are extremely sensitive to overcurrent. A resistor placed in series with a component ensures that current stays within safe operating limits.

Second, resistors control voltage levels. By arranging resistors in voltage divider configurations, engineers create precise reference voltages used by sensors, analog inputs, and feedback loops.

Third, resistors stabilize signals. In digital circuits, pull-up and pull-down resistors prevent floating inputs that would otherwise cause unpredictable behavior.

Fourth, resistors protect circuits. They absorb energy during transient events, helping to prevent damage from sudden voltage spikes.

Finally, resistors enable measurement. Current sensing resistors allow systems to monitor power consumption, detect faults, and manage battery life.

In short, resistors are the traffic controllers of electricity. Without them, circuits lose control. A solid starting point is this internal guide to basic electronics.

How Resistors Work at the Physical Level

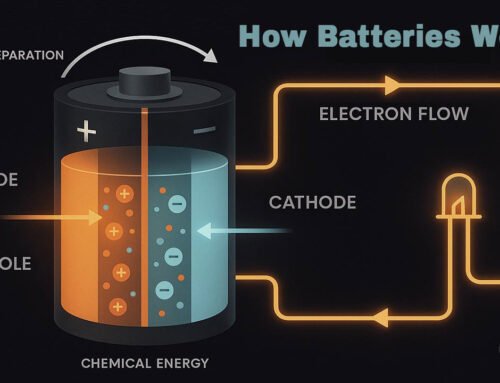

At the atomic scale, resistors work by impeding the movement of electrons. Conductive materials allow electrons to flow freely. Resistive materials introduce collisions and energy loss, converting electrical energy into thermal energy. The resistance value depends on three factors: material, length, and cross-sectional area. Longer paths increase resistance. Thinner paths increase resistance. Materials with higher resistivity increase resistance. Modern resistors are manufactured using carbon film, metal film, metal oxide, or thick-film deposition techniques. These processes allow precise control over resistance values and long-term stability. Heat dissipation is an unavoidable side effect. That is why resistors have power ratings. If too much power is dissipated, the resistor overheats, changes value, or fails completely.

Types of Resistors and Their Use Cases

Fixed resistors are the most common. Their resistance value is constant and defined during manufacturing. They are used for current limiting, biasing, and voltage division. Variable resistors, such as potentiometers, allow manual adjustment. These are common in volume controls, calibration circuits, and user interfaces. Thermistors change resistance with temperature. They are widely used for temperature sensing and thermal protection. Photoresistors change resistance based on light exposure. They appear in light-sensitive applications such as automatic lighting systems. Precision resistors offer extremely low tolerance and temperature drift. These are critical in instrumentation, medical devices, and aerospace electronics. Each resistor type exists because a specific control problem needs to be solved reliably.

Resistor Values, Tolerances, and Ratings

Resistance is measured in ohms. Values range from fractions of an ohm to millions of ohms depending on application. Tolerance defines how close the actual resistance is to its labeled value. A 5% tolerance resistor can vary significantly more than a 1% or 0.1% precision resistor. For analog and sensing circuits, tighter tolerances improve accuracy and repeatability. Power rating specifies how much heat a resistor can safely dissipate. Common ratings include 0.125W, 0.25W, and 0.5W. Exceeding this rating leads to thermal runaway and failure. Temperature coefficient describes how resistance changes with temperature. Low coefficients are essential in stable reference circuits. Choosing the correct resistor is not just about resistance value. It is about reliability under real operating conditions.

Resistors in Real-World Circuit Design

In digital electronics, resistors define logic states, terminate signal lines, and manage impedance matching. High-speed systems rely on carefully selected resistors to prevent reflections and data corruption. In analog electronics, resistors shape gain, frequency response, and signal linearity. Operational amplifiers depend on resistor networks to define behavior. In power electronics, resistors balance voltage across capacitors, discharge stored energy safely, and limit inrush currents. In embedded systems, resistors help microcontrollers read sensors, debounce switches, and manage communication lines. Across industries, resistors quietly ensure that complex systems behave predictably.

Common Mistakes When Using Resistors

One common mistake is ignoring power dissipation. Engineers often calculate resistance correctly but underestimate heat generation.

Another mistake is using low-tolerance resistors where precision is required, leading to drift and calibration issues.

Improper placement can also introduce noise, especially in high-frequency or analog circuits.

Finally, beginners sometimes assume resistors are interchangeable. In reality, construction type, temperature behavior, and stability matter significantly.

Good resistor selection is a hallmark of mature circuit design.

Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Final Thoughts

Resistors are not optional components or legacy technology. They are foundational tools that make electronic systems controllable, safe, and scalable. Understanding resistors means understanding how engineers shape electrical behavior to meet real-world constraints. Every reliable circuit begins with respecting current, voltage, and heat, and resistors are the components that enforce those rules.

Resources

- Horowitz, P. and Hill, W., The Art of Electronics, Cambridge University Press

- Boylestad, R., Introductory Circuit Analysis, Pearson

- IEEE Spectrum, Fundamentals of Electronic Components

Leave A Comment