DIY Hobby Maker’s Guide: How Mechanical Systems Work

How mechanical systems work, forces, motion, energy, simple machines, transmissions, linkages, bearings, tolerances, and common failure modes—then show you a repeatable design workflow so your 3D-printed gadgets, robots, and CNC add-ons run smoothly and reliably.

Table of Contents

- Big Picture: Force, Motion, Energy

- Simple Machines You Actually Use

- Motion Conversion & Power Transmission

- Linkages, Guides, and Constraints

- Friction, Bearings, and Lubrication

- Materials, Tolerances, and Fasteners

- Control: Open Loop vs. Closed Loop

- Reliability: What Fails and Why

- A Maker’s Design Workflow (Checklist)

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Big Picture: Force, Motion, Energy

Mechanical systems convert energy into useful motion while managing forces and constraints. Whether you’re building a camera slider, a pen plotter, or a pick-and-place head, the same ideas apply: where does power enter, how is motion guided, and what loads must the structure carry without bending, binding, or wearing out?

Newton’s trio in one line

F = m·a, Momentum changes with force, and every action has an equal and opposite reaction. In practice: if your carriage is heavy (big m), you need more torque (more F at a radius) for the same acceleration a. And when you speed up or stop, the frame feels the same load in the opposite direction—so brace it.

Simple Machines You Actually Use

- Lever: Gains force at the expense of distance; think servo horns or brake handles.

- Wheel & axle: Converts torque to linear speed at the rim; every roller, caster, or pulley.

- Pulley: Redirects force; with multiple sheaves it multiplies force (block and tackle).

- Inclined plane & wedge: Screws, cams, and knife edges are clever variations.

- Screw: Turns rotation into linear motion with large mechanical advantage; the heart of vises, Z-axes, and presses.

These are the atoms of mechanisms; everything else is a composition.

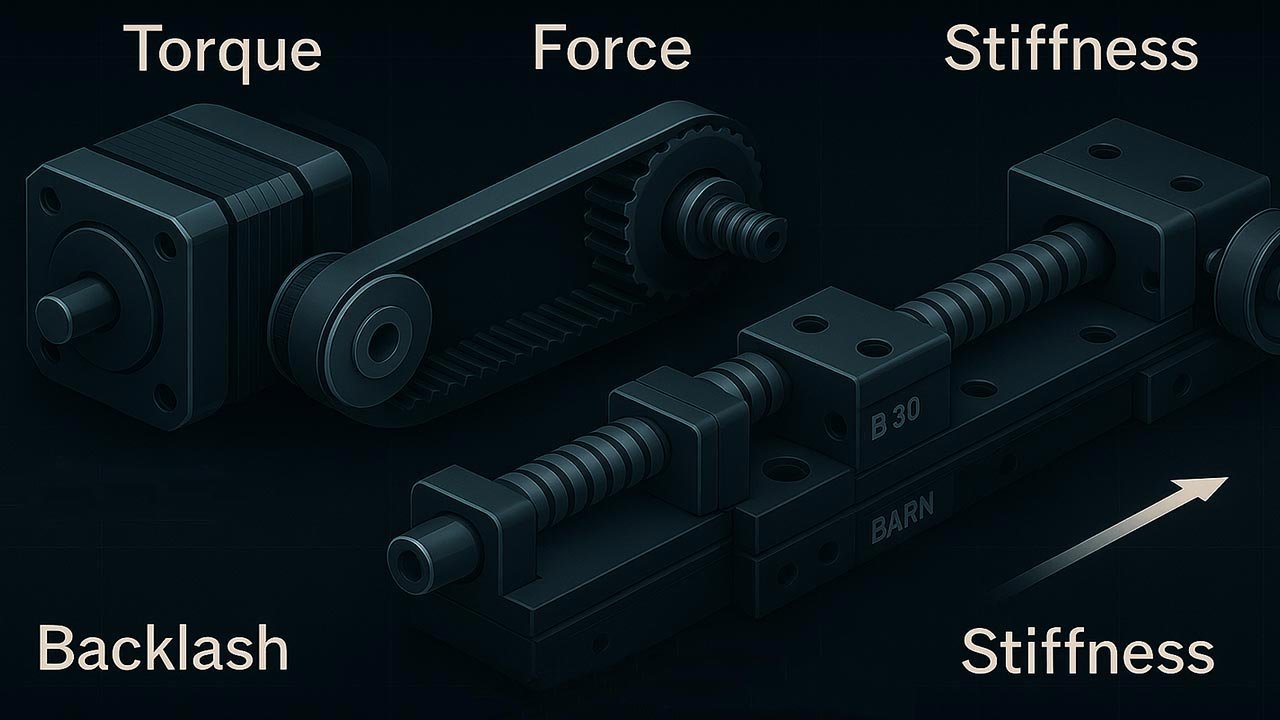

Motion Conversion & Power Transmission

Most maker builds start with a motor and need a specific speed, torque, and position at the output. You shape those with transmissions.

Gears and gear ratios

Ratio = driven teeth / driver teeth.

- A reduction (e.g., 60:20 = 3:1) multiplies torque by ~3 and divides speed by ~3 (minus losses).

- Backlash is the clearance between teeth; minimize it for precise positioning (use tighter modules, preload with split gears, or switch to timing belts or anti-backlash nuts).

- Planetary gearboxes pack high reduction into small volume with good alignment.

Belts, chains, and screws

- Timing belts (GT2/HTD): Quiet, cheap, tolerant of slight misalignment, and low backlash when tensioned. Ideal for XY gantries and camera sliders.

- Chains: Rugged and tolerant of dirt; better for outdoor or torque-heavy drives.

- Lead screws: Linear motion with high stiffness and self-locking; use anti-backlash nuts for repeatable positioning.

- Ball screws: Low friction and backlash, excellent for CNC; costlier and need lubrication.

- Rack & pinion: Large travel without long screws; useful for big tables and doors.

Linkages, Guides, and Constraints

Every body in 3D has six degrees of freedom (three linear, three rotational). Mechanisms constrain unwanted ones while leaving the motion you want.

- Linear guides: V-wheels on aluminum extrusion, MGN rails, drawer slides. Choose based on load, precision, and environment (dust, coolant).

- Rotary constraints: Hinges, bushings, ball bearings.

- Four-bar linkages: Convert rotation to near-linear motion or keep an orientation constant (think lamp arms, parallelogram plotters).

- Cam & follower: Custom motion profiles in a compact form—great for repeatable, timed actions.

A design that binds usually over-constrains motion or misaligns guides. Fewer, better constraints beat many mediocre ones.

Friction, Bearings, and Lubrication

Friction wastes power and generates heat. You control it with bearings and lube.

- Sliding bearings/bushings (PTFE/bronze): Simple, tolerant of dirt, good for low-speed or oscillating motion.

- Ball/roller bearings: Very low friction for continuous rotation; pick correct ABEC/precision grade for spindles.

- Preload: Slight axial or radial compression removes play and improves stiffness.

- Lubrication: Light oil for fast, small bearings; grease for heavier loads and sealing; dry PTFE when dust would gum up oil.

Materials, Tolerances, and Fasteners

- Material choice:

- PLA: easy to print, but creeps under load and softens with heat.

- PETG/ABS: better toughness and temperature.

- Nylon/CF-Nylon: high strength and wear resistance.

- 6061/7075 aluminum: stiff, machinable, great for frames.

- Steel: maximum stiffness and wear, but heavy; use sparingly where it counts (shafts, rails).

- Tolerances: Design mating parts with fits in mind (clearance, transition, interference). Add allowance for print shrink/swell; test coupons save time.

- Fasteners: Prefer socket-head cap screws for repeatable clamping. Use nylock nuts, thread-locker, or prevailing-torque nuts to resist vibration. Dowel pins and shoulder screws are for alignment and bearings, not just any bolt.

Control: Open Loop vs. Closed Loop

- Open loop: Stepper + belt + known microsteps; simple and cheap. It assumes no lost steps—fine for light loads.

- Closed loop (feedback): Add encoders (rotary or linear) or sensors (limit/home switches) so the controller measures and corrects. Use PID control to track a setpoint (speed, position, force).

Rule of thumb: if slipping, stalling, or precision matter, add feedback.

Reliability: What Fails and Why

- Misalignment: Drives binding, belts walking, premature bearing wear. Fix with square frames, shims, and parallelism checks.

- Overload/heat: Motors and plastics cook when torque is too high; use gear reduction, fans, or larger motors.

- Loosening: Vibration backs out screws. Use thread-locker and mechanical locking features.

- Wear & contamination: Dust kills rails and belts; add covers and choose sealed bearings.

- Resonance: Frames shake at certain speeds; increase stiffness, add mass, or change speed profile (jerk/accel limits).

A Maker’s Design Workflow (Checklist)

- Define the job: required force/torque, travel, speed, accuracy, duty cycle.

- Choose motion type: rotary, linear, or both; decide on guides and constraints.

- Select transmission: belt, screw, gears—compute ratio for target speed/torque.

- Size the motor: back-calculate torque from load and acceleration; add 30–50% margin.

- Lay out structure: shortest load paths, triangulate, and keep rails co-planar.

- Specify fits & tolerances: include clearance for bearings, press fits for pulleys, and alignment features.

- Plan maintenance: access to fasteners, lube points, belt tensioners, and homing switches.

- Prototype, measure, iterate: check squareness, backlash, runout, temperature, and current draw under load.

- Document: BOM, settings (current limits, accel), assembly notes, and failure learnings.

Leave A Comment