Master Boot Record vs GUID Partition Table: A Comprehensive Technical Comparison

This article explores the structural, architectural, and operational differences between Master Boot Record (MBR) and GUID Partition Table (GPT), offering technology managers the insights needed to optimize storage infrastructures. It breaks down how each system handles performance, reliability, scalability, boot mechanics, and long-term innovation demands.

Table of Contents

- Overview

- MBR vs GPT Timeline

- MBR vs GPT Comparison Table

- 1. Architecture Fundamentals

- 2. Storage Capacity & Partition Limits

- 3. Reliability, Redundancy & Data Integrity

- 4. Compatibility, Boot Modes & OS Support

- 5. Security Considerations & Innovation Trends

- 6. Strategic Use Cases for MBR vs GPT

- 7. Migration Considerations & Best Practices

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

- Final Thoughts

- Resources

Overview

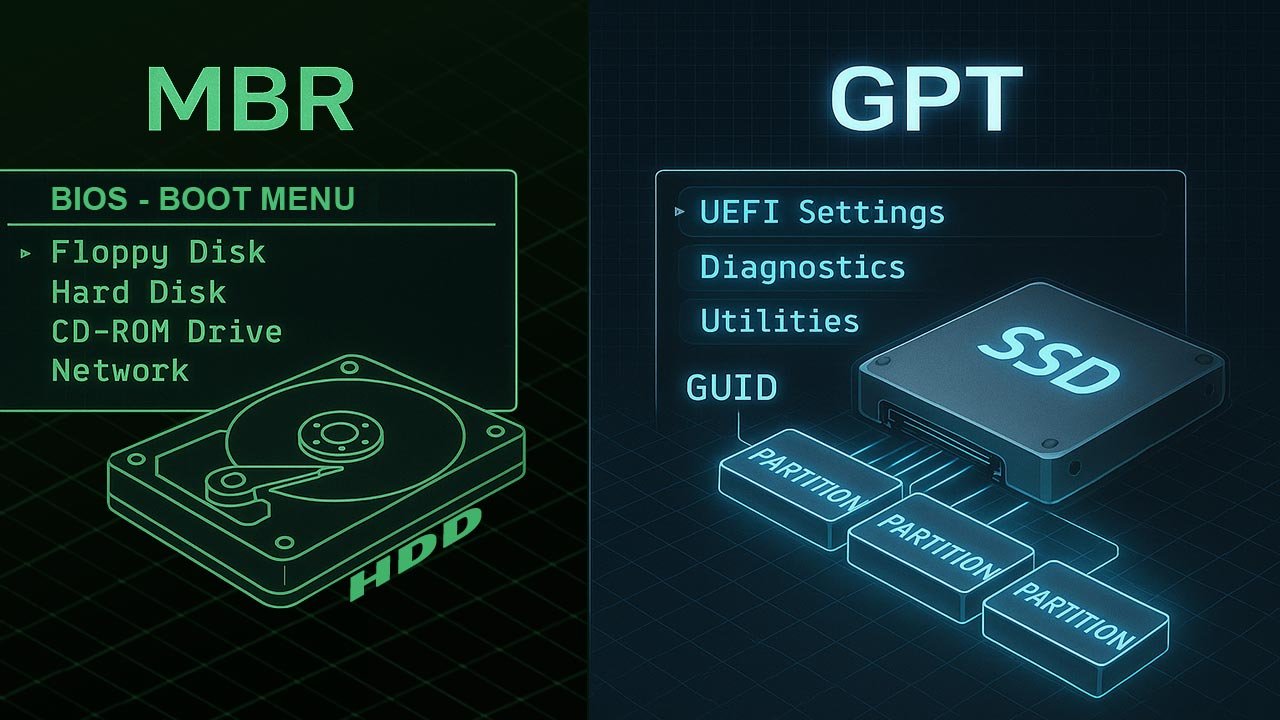

MBR and GPT are the two dominant disk-partitioning standards that determine how storage devices organize partitions, locate boot loaders, and maintain system integrity. Introduced in 1983, MBR was built for early personal computing. GPT, standardized around 2000 under the UEFI specification, was engineered for the modern era of large drives, fault-tolerant architectures, and firmware-level security.

Understanding their differences is essential for storage architects, IT managers, and systems engineers who must carefully select a partitioning scheme that fits long-term infrastructure requirements.

MBR vs GPT Timeline:

| Technology | Year Introduced | Actively Used | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBR | 1983 | 1983–present | Legacy but still supported; BIOS-dependent |

| GPT | 1999–2000 | 2000–present | Modern standard; UEFI-based; supports very large disks |

Master Boot Record (MBR)

- Introduced: 1983

- First implemented in: IBM PC DOS 2.0

- Primary era of use: 1983 – present (still used on legacy systems)

- Peak relevance: 1980s–2000s (BIOS-based PCs)

- Current status: Still supported, but considered legacy and increasingly phased out in modern systems.

GUID Partition Table (GPT)

- Introduced: 1999 (early Intel EFI specification)

- Standardized with UEFI: 2000–2005 (as UEFI matured)

- Primary era of use: 2005 – present

- Current status: Modern default for new systems, especially those using UEFI, NVMe, Secure Boot, large disks >2TB, and enterprise infrastructure.

MBR vs GPT Comparison Table:

| Feature | Master Boot Record (MBR) | GUID Partition Table (GPT) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Disk Size | Up to 2 TB | Up to 9.4 ZB (zettabytes) |

| Max Partitions | 4 primary (or 3 + 1 extended) | 128 partitions standard (scalable) |

| Boot Mode Requirement | BIOS | UEFI |

| Backup Ability | No built-in backup of partition metadata | Primary & secondary (end-of-disk) GPT headers |

| Performance Details | Performs well on small, legacy disks; limited addressing reduces I/O efficiency on large drives | Optimized for large disks; 64-bit LBA improves throughput and indexing performance |

| Error Detection | No CRC protection | CRC32 checksums for metadata integrity |

| OS Compatibility | Universally supported; default for older systems | Required for newer systems using UEFI Secure Boot |

| Security Features | None | UEFI Secure Boot integration, protective MBR for safety |

1. Architecture Fundamentals

MBR and GPT differ fundamentally in how they map physical addresses, locate boot instructions, and store partition data. These architectural differences influence performance, reliability, scalability, disaster recovery, and OS compatibility.

MBR Internal Structure

MBR occupies the first 512 bytes of a disk. It contains the boot loader, disk signature, and a small partition table with four entries. Because all functional logic depends on a single sector, MBR is vulnerable to corruption. Its 32-bit addressing restricts total available disk space and limits how efficiently storage systems manage partitions at scale.

GPT Internal Structure

GPT uses 64-bit LBA addressing and distributes its metadata across multiple sectors, including a primary header at the disk’s beginning and a secondary header at the end. These structures enable error detection, improved scalability, and redundancy. Each partition receives a globally unique identifier (GUID), providing clear mapping across diverse OS ecosystems and distributed computing environments.

2. Storage Capacity & Partition Limits:

| Technology | Max Disk Size | Max Partitions |

|---|---|---|

| MBR | 2 TB (one terabyte is equal to 1,000 gigabytes) | 4 primary (or 3 + 1 extended) |

| GPT | 9.4 ZB (one zettabyte is equal to a trillion gigabytes) | 128 partitions standard (scalable) |

MBR’s 2 TB ceiling stems from its 32-bit addressing limitation. As data-intensive industries move into multi-petabyte systems and NVMe-based infrastructures, GPT’s 9.4 ZB addressing range becomes essential.

Enterprise systems increasingly require dozens of partitions—boot, recovery, snapshots, hypervisor spaces, containers—driving further demand for GPT’s high partition count.

3. Reliability, Redundancy & Data Integrity

Reliability is one of the starkest contrasts between MBR and GPT.

MBR contains no redundancy, so corruption of the first sector can render the entire disk unbootable.

GPT, however, includes:

- A primary header

- A mirrored secondary header

- CRC32 checksums for metadata validation

- Protective MBR that blocks legacy software from overwriting GPT structures

These design decisions significantly reduce the likelihood of catastrophic disk failure and simplify disaster-recovery workflows.

4. Compatibility, Boot Modes & OS Support

MBR boots exclusively in BIOS mode, making it ideal for older hardware. GPT requires UEFI firmware for booting, though many operating systems support GPT-formatted secondary drives under BIOS.

Modern OS ecosystems increasingly push GPT adoption because UEFI supports Secure Boot, faster initialization, and cleaner firmware-level device enumeration.

5. Security Considerations & Innovation Trends

MBR predates hardware-embedded security, making it incompatible with modern trusted-execution environments. GPT integrates seamlessly with UEFI Secure Boot, which prevents unauthorized boot loaders from executing and reduces the attack surface for rootkits.

Innovation trends favor GPT due to its:

- Higher metadata integrity

- Standardization under UEFI

- Compatibility with emerging storage buses (NVMe, PCIe 5.0, CXL)

- Future-proof GUID-based partitioning

MBR is effectively frozen in time, while GPT continues to evolve along with firmware advancements.

6. Strategic Use Cases for MBR vs GPT

MBR is still suited for:

- Legacy BIOS-only devices

- Older embedded systems

- Backward-compatibility testing environments

- Simple drives under 2 TB

GPT is ideal for:

- Modern enterprise servers

- NVMe-based high-performance systems

- Multiboot architectures

- Virtualization and container hosts

- UEFI-secured workstation fleets

Technology managers should align their choice with long-term hardware roadmaps, firmware support cycles, and organizational security policies.

7. Migration Considerations & Best Practices

Migrating from MBR to GPT requires careful planning, especially for systems hosting mission-critical workloads. Best practices include:

- Create full disk images prior to conversion

- Validate UEFI compatibility on target hardware

- Update firmware before performing conversions

- Use official OS tools (Windows mbr2gpt.exe, Linux gdisk)

- Test Secure Boot impact on custom boot loaders

For organizations modernizing aging infrastructures, moving to GPT standardizes storage across all systems and prepares platforms for next-generation security and performance demands.

Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Final Thoughts

The most important takeaway is that GPT is not merely a replacement for MBR—it is a modern architecture built for the demands of scalable storage, hardware-level security, and enterprise-grade reliability. While MBR remains relevant for legacy systems, GPT should be the default choice for future-oriented infrastructure. Its redundancy, metadata integrity, GUID-based partitioning, and UEFI integration deliver measurable benefits for system resilience, performance, and long-term sustainability.

Resources

- UEFI Specification

- Microsoft Docs – GPT vs MBR

- Linux GPT Documentation

- Intel EFI Developer Resources

Leave A Comment