Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

DIY Hobby Maker’s Guide: How Do Computers Work

How do computers work? The CPU and memory team up, what the operating system actually does, and how input/output completes the loop—so you can debug smarter, choose parts confidently, and build projects that run like a champ.

Table of Contents

- Big Picture: From Input to Output

- Bits, Logic, and Transistors

- The CPU: Fetch–Decode–Execute

- Memory vs. Storage (and Why It Matters)

- Operating System: The Traffic Controller

- I/O: Talking to the Outside World

- Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions

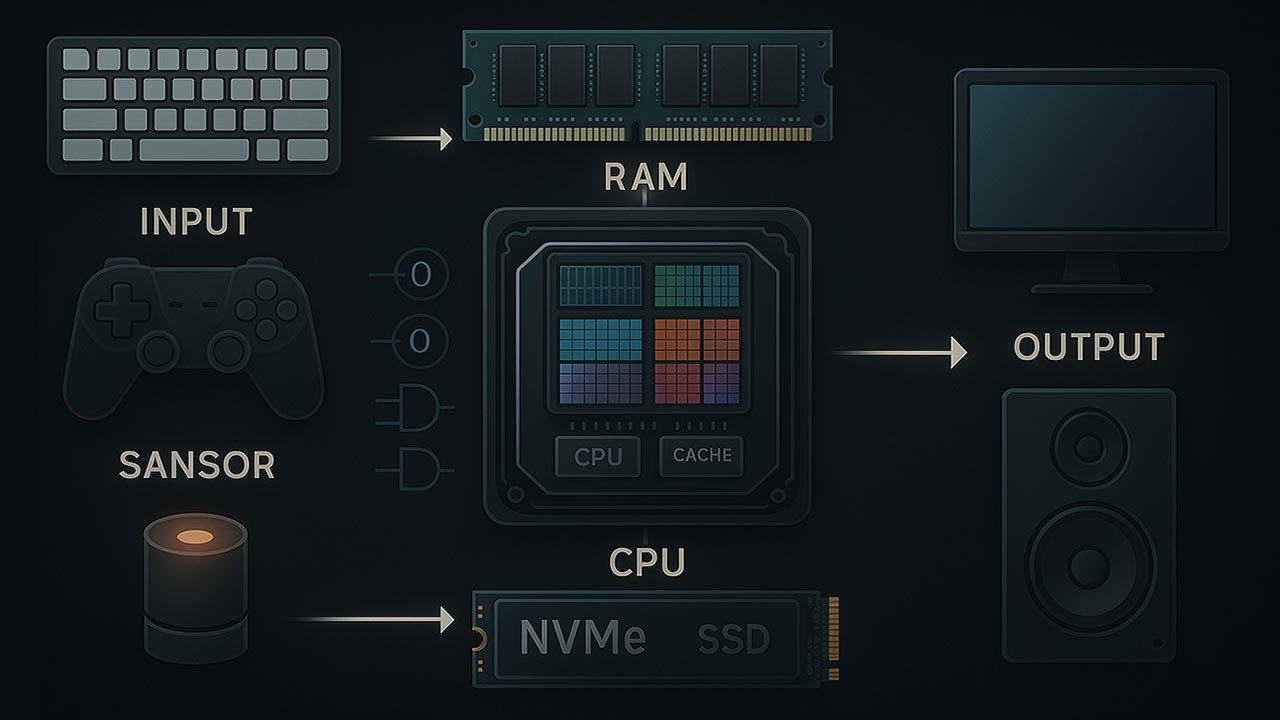

Big Picture: From Input to Output

Computers transform input into output by following a tight loop: you provide data (keyboard click, sensor reading), the machine processes it using instructions, and then it outputs results (pixels on a screen, signals to a motor). Under the hood, all of this is patterns of 0s and 1s flowing through circuits at dazzling speeds.

The Information Pipeline

- Input devices turn physical actions into digital signals.

- Processing happens in the CPU (with help from memory and storage).

- Output turns digital results into something useful—graphics, sound, motion.

- Control software (the operating system) orchestrates everything.

Bits, Logic, and Transistors

Computers are fundamentally switches. A closed switch can represent 1, an open switch 0. Billions of such switches—transistors—form the basis of digital logic.

Binary & Boolean Logic

Binary data is manipulated with Boolean algebra—operations like AND, OR, and NOT. Combine these, and you can build adders, comparators, multiplexers, and complete CPUs. This is the bridge between math and hardware.

Logic Gates Built from Transistors

A logic gate is a tiny circuit that implements a Boolean function. Gates are built from transistors arranged so that when inputs change, the output flips according to the rule (e.g., AND is 1 only if both inputs are 1). Chaining many gates yields complex units like arithmetic/logic units (ALUs) and control circuits. For a maker, this matters when designing with 74xx logic, FPGAs, or microcontrollers: you’re ultimately orchestrating logic gate behavior.

The CPU: Fetch–Decode–Execute

The central processing unit (CPU) runs a tight rhythm called the fetch–decode–execute cycle. It’s the heartbeat that turns stored instructions into actions.

Instruction Cycle

- Fetch: Grab the next instruction from memory (pointed to by the program counter).

- Decode: The control unit interprets the instruction—what operation and which operands.

- Execute: The ALU performs the operation; results may update registers or memory.

This loop repeats billions of times per second, which is why even simple instructions add up to complex behaviors.

Registers, Cache, and Clock

- Registers are ultra-fast storage inside the CPU used for immediate values and addresses.

- Cache (L1/L2/L3) holds recently used data/instructions to avoid slower memory trips.

- The clock provides the tempo; modern CPUs also exploit pipelining (overlapping stages) and parallelism (multiple cores, vector units) to increase throughput.

Memory vs. Storage (and Why It Matters)

RAM (memory) is the CPU’s “workbench”: fast, volatile, and limited in size. Storage (SSD/HDD) is the long-term “warehouse”: slower, non-volatile, and much larger. Programs and data are loaded from storage into RAM before the CPU can work on them. More RAM reduces slow trips to storage; faster storage (like NVMe SSDs) shortens load times but still can’t match RAM’s speed. Understanding this helps makers pick parts wisely and tune performance.

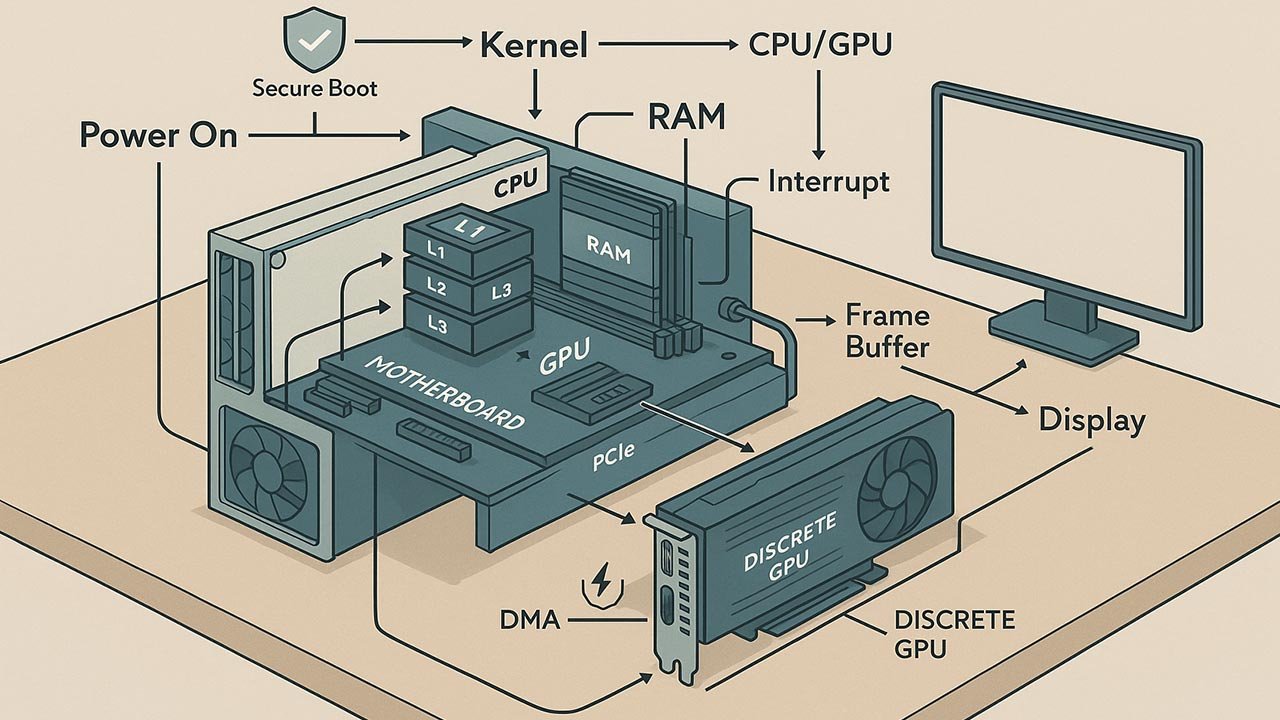

Operating System: The Traffic Controller

The operating system (OS) sits between your apps and the hardware, handling messy details—like who gets CPU time, how memory is shared safely, and how devices are accessed uniformly.

The Kernel’s Day Job

At the center of an OS is the kernel, which:

- Schedules processes/threads so programs share the CPU fairly and responsively.

- Manages memory, including virtual memory and protection so apps don’t clobber one another.

- Brokers I/O via device drivers and a uniform API (system calls).

- Runs early at boot, then stays resident to supervise everything.

For hobby projects (Raspberry Pi, microcontrollers running lightweight OSes), knowing what the kernel does clarifies why timing, permissions, and drivers matter.

I/O: Talking to the Outside World

Input/Output (I/O) subsystems connect your computer to reality. Keyboards, displays, cameras, sensors, actuators, and network cards speak through buses and protocols (USB, PCIe, I²C, SPI). Drivers translate OS requests into device-specific commands; interrupts signal the CPU when devices need attention. Makers should map out I/O early: bandwidth, latency, and driver support can make or break a build (e.g., camera frames over USB vs. CSI; SPI speed for LED matrices; PCIe lanes for GPUs or NVMe).

If you remember one thing, make it this pipeline view: inputs → CPU (with registers, cache) ↔ RAM ↔ storage → outputs, all choreographed by the kernel. With that mental model, you can reason about bottlenecks (CPU vs. memory vs. I/O), pick components that complement each other, and debug systematically: measure where time is spent, reduce cache misses, avoid needless disk I/O, and let the OS work for you—not against you.

[…] To understand what “signals” and “triggers” look like in computers, visit: How Computers Work. […]